Sri Lanka 2017: History, Beaches and Parks

By the third day of morning walks on the ramparts of Galle’s fort, I was on nodding terms with regular exercisers. One of them stopped me to chat, asked where I came from, what I doing in Sri Lanka, and what I did for a living. My answer to the last question, that I had worked as an international economist, prompted a discussion about Sri Lanka. “We had a chance to develop rapidly, a great geo-political location, small, educated population, could have been like Singapore”. I agreed, but added the opportunity still existed. “Yes, but these bloody politicians are making a mess of it”. I acknowledged not following the country’s politics closely, but agreed that politicians are a barrier to sensible governance in many countries.

Sunset, Galle

Sri Lanka has been in my head ever since I heard bedtime stories from the Ramayana, an Indian epic. The evil Ravana abducted Sita, the virtuous wife of exiled Prince Rama, and whisked her off to Lanka, the country’s ancient name. Rama and his brother Laxmana raised an army with the help of Hanuman, the monkey-god, invaded the island, killed Ravana and recovered Sita, her virtue intact. I visited Sri Lanka briefly for work in 2004 when the country was still embroiled in a civil war. Security was tight and barricades and troops surrounded the main buildings in Colombo to protect against terrorist attacks. It wasn’t a congenial time to wander around the country.

Fresco, Sigiriya

The country had been progressing well until it was hobbled by a three-decade long civil war in the Northeast part of the island that was finally resolved in 2009 with carnage. Nevertheless, despite that crippling setback, Sri Lanka has twice the income per person and a much better human development index ranking (measures a long, healthy, knowledgeable life with a good income) than its giant neighbor, India. Indeed, it is better off and better managed than any other South Asian country, although that may not be saying much.

I had a sense from the Ondaatje’s novels that the island’s culture was woven with many strands. Arab traders began to settle from the 7th Century onwards, intermarrying to spawn a strain of Sri Lankan Moors who are Muslim. The Portuguese arrived in the at the beginning of the 16th Century and dominated the coastlines for 150 years when the Dutch supplanted them, also for about 150 years, both leaving the hill-kingdom of Kandy under Sri Lankan rule. Then the British supplanted the Dutch and ruled the whole island for also about 150 years. The progeny of European intermarriages with locals are called Burghers, mostly Catholics, because the Portuguese brought priests, but some adhere to the Dutch Reform Church and Church of England.

Frescio, Sigiria

Although there are physical, cultural and racial remnants from the colonial era, the enduring influence on the island is from India. The Sinhalese language is a part of the Indo-Aryan family and its script is derived from Brahmi, which was used in ancient India. In legend, a wayward, exiled Indian prince from North India settled in the island in the sixth century BCE, mixing with the indigenous people. Later, migrants from Eastern India sailed in. Still later, South Indians arrived, some as conquerors of Northeast and others as traders. Their descendants are called Sri Lankan Tamils. During British rule, Tamils were brought in to work on rubber and tea plantations, known as Plantation or Indian Tamils.

Around 250 BCE, in legend, Emperor Ashoka’s son and daughter, both Buddhist monks, came to Sri Lanka as missionaries and converted King Devanampiya Tissa and his family to that religion. Buddhism has endured in Sri Lanka and is still followed by 70 percent of the population, while 13 percent are Hindu, 10 percent Muslim and 7 percent Christian.

Unlike in Singapore where the threads of many cultures have woven a vibrant and energetic tapestry, in Sri Lanka they hardened to spread apart and cause violent conflict. Even though the war has ended, accusations of war crimes on both sides keep the embers of the conflict aglow. The country now has a chance to heal and move on to provide a better life for all its citizens.

Colombo

As Colombo has the island’s only international airport, it’s the best place to start exploring the country. The city has a population of about three-quarters of million people, but the larger metropolitan area has just shy of 6 million. Many of them work or travel to the city daily so the traffic is snarled, but thankfully, unlike India, drivers follow traffic rules better and don’t use their horns as much, avoiding the grating cacophony.

My driver-guide took me around to the main sights mentioned in the guidebook: along Galle Face green; the almost non-existent fort; the Pettah market area with an unusually colorful mosque; past British era buildings; the Independence Memorial; and around Viharamahadevi park. I lingered at the National Museum, an imposing Italianate building erected by the British. Its renowned 17th Century royal throne, 9th Century Buddha statue and bronze Boddhisatva sandals made the visit worthwhile. The adjoining National Art gallery, with just one poorly lit room of unexceptional paintings did not require much time, but the street outside had 100 yards of colorful paintings, realistic and abstract, hung on railings and placed on the street.

I was lucky to arrive on Navam Full Moon Poya Day, which commemorates the appointment of the first Buddhist Council when Buddha announced the code of fundamental ethics for monks. It is a major event for Buddhists and celebrated in the evening with a parade of colorfully caparisoned elephants and troops of folk dancers, jugglers, fire-eaters from many parts of Sri Lanka, slowly moving around the Gangaramaya Temple complex situated close to Beira Lake. Too late to buy a ticket for a close up view, I managed to squeeze onto an elevated stand and got a decent look. I returned the next day to walk around the temple’s many buildings that include a relic chamber, library, education halls, residences, a Bodhi tree, and a museum exhibiting gifts.

I was lucky to arrive on Navam Full Moon Poya Day, which commemorates the appointment of the first Buddhist Council when Buddha announced the code of fundamental ethics for monks. It is a major event for Buddhists and celebrated in the evening with a parade of colorfully caparisoned elephants and troops of folk dancers, jugglers, fire-eaters from many parts of Sri Lanka, slowly moving around the Gangaramaya Temple complex situated close to Beira Lake. Too late to buy a ticket for a close up view, I managed to squeeze onto an elevated stand and got a decent look. I returned the next day to walk around the temple’s many buildings that include a relic chamber, library, education halls, residences, a Bodhi tree, and a museum exhibiting gifts.

On my flight from Delhi, I chatted with a pediatrician returning from a conference. Two days later, I met her son at the Sinhalese Sports Club, primarily a cricket club, Sri Lanka’s most popular sport, and both legacies of British rule. We talked about the value of an MBA degree. As I had been a professor at a business school earlier in life, his mother thought that he would benefit from a conversation with me. He had analyzed his situation well so we chatted about Sri Lanka instead. He saw it as becoming an integral part of the Asian and global economy in his lifetime, which I think is entirely possible.

After Colombo, I criss-crossed the country, except for the East coast, up to the tip of the Northeast above Jaffna and down to Galle in Southwest, including the “cultural area” (Kandy, Dambulla, Sigiriya, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura and Mihinthale) in between. The roads throughout were good, but with just one lane each way. As buses and lorries also use them, the pace was slow, averaging 30 miles per hour. Patience and passing skills are essential for drivers.

It took an hour to just get out of Colombo to open country where the road wound through villages and towns and the vegetation, always lush green, was dominated by rubber plantations in the early going, and tea as we began to climb. Tea bushes are trimmed lower and much more densely packed than in my memory of Darjeeling, but still hand picked. I wondered how pickers moved through rows. It looked like hard work, bending over low for hours. Small roadside stalls offered fresh coconut water to drink—select a coconut, the top is chopped off, drink the water with a straw, the coconut is cut open, a piece sliced off to make a spoon with which to eat the flesh. We stopped for lunch at a lodge used by the crew that filmed “Bridge over River Kwai”. Looking down at the fast-flowing Kelani River from the dining room up on a hill, one could imagine the bridge being built over it.

Tea Gardens, Nuwara Eliya

Nuwara Eliya

The higher we climbed, the more beautiful the scenery became. Carpets of green bushes covered the hills that descended to narrow valleys with streams flowing through. I was reminded of the Douro Valley in Portugal, but that had vines, not tea bushes. We reached Nuwara Eliya at about 6,000 ft elevation in the early afternoon. Many imposing British Tudor style buildings anchor the town, including the Hill Club where I lodged, but there were cottages too, and new construction that dominated the view.

Before the British left, the town must have looked like an English village with a golf course, racecourse and a lake, overlooked by Sri Lanka’s highest mountain at 8,200 ft. For them, it was a reprieve from the coastal heat and humidity and a sanctuary for planters and civil servants to relax, play golf and cricket and hunt. The climate was conducive to growing “English” fruits and vegetables and tea, for which the area still remains renowned. In keeping with pukka British tradition, I was loaned a tie and jacket to use the bar and dining room at the club. I chatted with a couple from Australia of Swiss-German origin, who turned out to be good friends of a former colleague when I worked as an economist. Small world.

I was up at an absurdly early hour the next morning to drive in a rickety vehicle with no heat to arrive at Horton Plains National Park, at about 7,000 ft elevation, at 7 am. The line to get entry tickets was dauntingly long as there was only one clerk. Tourists shivered in the cold. For me the wait was not worth the reward. Yes, the 7 mile hike was interesting, walking through mostly a bare, grassy landscape interspersed by clumps of forest, which were more interesting, and the view from Lands End, a sheer drop of about 3,000 ft, was awesome. I did not see much wildlife during the hike, except a few deer and langurs at Baker Falls.

Tea Gardens, Nuwara Eliya

Kandy

The scenery along the drive north from Nuwara Eliya to Kandy was more lush and interesting than the route up from Colombo, although still hills covered with tea bushes at higher elevations, and paddy fields as we descended. Kandy is the second largest city and the seat of the last king of Sri Lanka. We arrived just in time to watch a spectacular sunset from Amaya Hill above town, a fiery bowl with a wide red halo descending over the ridge, capturing the trees and houses in silhouette.

Kandy from Amaya Hill

The kingdom held the Portuguese and Dutch at bay for three centuries, but succumbed to the British partly because of a coup organized by courtiers. It is home to the Tooth Temple that houses the Buddha’s tooth as a relic, and is located by a lake in the center of town, coexisting there with British era buildings.

The temple is actually a complex of buildings that include the royal palace, audience halls and museums. Soon after entering there is alter framed by four huge elephant tusks and a large red tapestry telling a story and ceiling painted with intricate and ornate designs. The relic is sequestered in an inner stupa and is not on display. I found the International Buddhist Museum most interesting as it told the story, in objects and commentary, of the spread of Buddhism in Asia.

It began to rain just as I finished my visit, but lightly enough for me to make a hasty walk to the Kandy Arts and Cultural Center nearby. I enjoyed a hour-long lively performance of a variety of traditional Kandyan dances, with men and women in colorful costumes and headdresses accompanied by drums and cymbals. By the time the performance ended the rain had become a tropical downpour. I was saved from being drenched by my savvy driver who found a parking spot just 20 feet from the exit.

Dancers, Kandy

Before leaving for Sri Lanka’s main archeological sites, I walked through the 150 acre botanical garden bordering the Mahaveli River just outside Kandy. It had areas for local spices, orchids, indigenous flowers and avenues lined with varieties of palms. As it was early, and visitors were sparse, it was possible to sit and calmly enjoy the colorful flora and the sound of birds. I spotted an Ashoka tree in flower to photograph.

Ancient Sites

The road to the Dambulla Royal Rock Temple, my first stop in the cultural area of Sri Lanka, has spice gardens on both sides that my driver pointed out, but honestly, even after visiting the botanical garden, I couldn’t make out a cinnamon from a pepper tree.

I made the mistake of eating lunch before starting the climb up to the Dambulla cave temples. After a thousand steps up in the midday heat, I reached the entrance only to be told I needed a ticket. “There was no ticket office at the base”, I said. “Its at the entrance on the other side. You have to go down and get one.” Exhausted, I rebelled and decided that if I went down, I would not come up again. Fortunately, other tourists had the same problem so we split the cost of a runner, who got tickets for us–a neat way of making extra money.

Fresco, Dambulla

The five main caves are spectacular. Some have been used for worship since before the Common Era. They house more than a hundred statues of Buddha and a few of kings, and stunning ceiling frescoes covering over 2,000 sq. yds., according to my guidebook. I walked through the caves twice to more fully appreciate the magnificent art. In between, I took in the view of the countryside and the rock fortress of Sigiriya, about 15 miles away, which was my next stop.

The top of Sigiriya (Lion Rock) is a 652 ft climb up steps hewn into the rock. A visitor has to be fit to appreciate Sri Lanka’s ancient sites. Several hundred school girls preceded me, making for slow going. When John Still discovered Sigiriya in 1907, he said that the whole western face of the rock, about 460 x 130 ft had been a gigantic picture gallery. Now just a fraction remains in a walk-through cave, vividly colorful frescoes of beautiful women. Since it’s a single file line of visitors passing by the paintings, it’s not possible to linger for long, unfortunately. The exit is to the “mirror wall” that was at one time so polished that the king could see himself as he passed by, but no longer. Further up is a flat area where two huge lion’s paws carved into the rock border the steps going up to the ruins of the fortress. I rested there for a while pondering the next climb and amused by watching Buddhist monks taking selfies. In the end, I decided to turn back because the long line was ascending the steps ever so slowly and the guide book said that there wasn’t much to see up at the top.

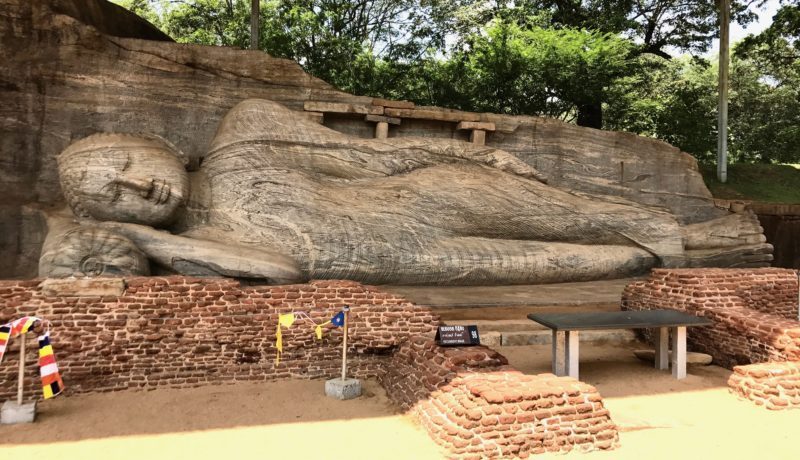

Buddha, Polonnaruwa

Polonnaruwa was the seat of Sri Lanka’s main kingdom from the 12th Century for a couple of hundred years. The museum and archeological ruins are spread over a large area, needing transport between them. King Parakramabahu was the main builder, but his successor, Nissankamalla also contributed structures. The area includes palaces, audience halls, stupas and a huge lake to irrigate the surrounding land. The Vatadage has fine moonstones at entrances and four serene Buddha statues in the center; the unremarkable Hatadage nearby once housed Buddha’s tooth relic; and the stone book, 30 feet long and 5 feet wide, sings Nissankamalla’s praises. After a bloody start, he partly adopted Emperor Ashoka’s governance style and is thought to have influenced the rulers of Pagan in Myanmar. To the north, is the Gal Vihara with beautifully carved huge Buddha statues in meditative, standing and parinirvana poses. Further, the Lankatilika temple, which looks like a church with adorned figures carved in niches along the outer wall, and the tall, headless standing Buddha in the nave, is especially impressive. The archeological museum and the plaques outside each site were informative.

Moonstone, Polonnaruwa

Later that day, I went on a game drive in the nearby Minneryia National Park. We saw a large family of about 15 elephants guarded by pelicans at a reservoir. Further on the drive, we also saw three smaller families and the odd loner wandering around. Other than the majestic elephants, we sighted deer and a mongoose crossing out path.

Minneriya National Park

Jaffna

Instead of visiting Anuradhapura-Mihintale nearby, we headed North to Jaffna to ease, logistically, our journey South later. Historically, the Jaffna area was an independent kingdom, ruled by South Indians on and off for periods. The Europeans dominated since the 16th Century though. After they left, Jaffna was the second most populous city in the country. Sri Lankan Tamils dominated its population, but Moors, Burghers, and Sinhalese also lived there.

Without going into the complex reasons for the civil war, the Jaffna peninsula was where most hostilities occurred and Tamil rebels occupied the city on and off. Many residents left for safer parts of the country or abroad, a large diaspora. One of my former colleagues in Washington DC was a Sri Lankan Tamil who represented the country in Davis Cup tennis.

Even though the rebellion was defeated in 2009, and much of the damage to the city has been rebuilt, its population has not recovered and remains 12th largest in the country. After entering the province, an increase in military presence was noticeable as were the number of highway patrols, which, by the way, were present on every major road. I also noted that the country was not as lush and densely planted as other parts of Sri Lanka we had driven through. My former colleague had explained that the area’s poor agricultural prospects had led Tamils to concentrate on education, leading to good careers that brought on resentment from the Sinhalese–a touchy topic I will leave alone.

My hotel was in the center of town. On the way in, I noticed a few well-kept churches that surprised me as I anticipated a dominantly Hindu population. As I later learned, these religious buildings hailed back to the Portuguese period. I could see from my room window the stately, white library with Islamic domes, reminiscent of Baker and Lutyen’s structures in New Delhi, and the landmark clock tower that looks like a minaret, but was built by the British. I walked along the ramparts of the Portuguese-Dutch fort, although not much of it remains, but enough to have been used as an encampment for the forces of all sides of the civil war.

The afternoon’s main attraction was a puja (prayer) in the huge Nallar Kovil, a Hindu temple built in the South Indian style with three monumental, pyramid-like golden gopurams (towers) studded with statues of deities. Inside the vast compound were alcoves with deity images or enormous, gaudy religious paintings. Male visitors had to take their shoes and shirts off to enter. For the puja, the main deity image, placed on a silver peacock resting on a trolley about 4’x4’, was wheeled by a band of priests slowly for about 50 yards, while they beat drums loudly, blew into a shehnai (like an oboe), clanged huge brass bells, followed by about a hundred devout worshipers. The image was carried into a small inner sanctum and placed there. The priests returned to distribute water to waiting worshipers who were clearly engrossed in the proceedings, touching ears with crossed hands and bowing.

Buddha, Polonnaruwa

Anuradhapura

The next morning, before driving to Anuradhapura, we meandered up the coast to Mathagal, where in legend, Sanghamitta, Emperor Ashoka’s daughter, is thought to have landed in Lanka. She is revered for bringing with her a sapling of the Bodhi tree from Bodhgaya, where Buddha was enlightened, and for establishing the Bhikkuni (nun) order in the country. We had to skirt around a crowded Christian celebration to reach the spot where a modern memorial has been erected and a Bodi tree planted to honor her.

We made our way to Mihintale (Mahinda’s Mountain) where I had to climb another thousand steps to reach the stupa commemorating the spot where, in legend, the monk Mahinda, Emperor Ashoka’s son, first met the King of Lanka, Devanampiya Tissa, who was on a hunt. They engaged in a discussion that eventually led to Tissa’s conversion to Buddhism. A statue of Tissa adorns the stupa that is at the center of three small steep hills, one has a stupa enclosing Mahinda’s remains, another a huge modern statute of Buddha in meditation and the third a viewing platform.

Nearby Anuradhapura was the capital of Sri Lanka for about a millennium from the 4th Century BCE onward. It has many ruins and museums. Sanghamitta’s sapling has flourished uninterrupted for over two millennia and is revered as the Mahabodhi tree. I visited in the evening together with many worshipers who surrounded the lit tree. Their silent prayers and offerings created a spiritual and meditative mood, heightened by the rows of lamps nearby, along the path to another temple.

On the next morning, I wandered through most of the ruins and museums spread over a large area. Most appealing were the Thuparama stupa, first built by Devanampiya Tissa in the 3rd Century BCE and the small stupa-mound next to it that supposedly contains Sanghamitta’s ashes; and the two enormous Abhayagiri (1st Century BCE) and Jetvanarama (3rd Century CE) stupas, among the largest structures of the ancient world on the scale of the pyramids at Giza, with adjoining monasteries that housed thousands of monks in ancient times.

Lankatilika, Polunnaruwa

Galle

In the afternoon, we drove to Galle, at the Southwestern tip of the island. The long distance was covered in less time than usual by using the only two toll highways in the country, from the international airport to Colombo, and from the city to Galle. Unfortunately, the two are not connected, costing 45 minutes to traverse the city from one to the other. But fortunately, the best Alfonso mango stall was on the way and we stopped to buy some. The empty southern highway cuts through lush rice paddies and rubber plantations, a different vista from the Northeast.

I lodged in the fort area, separated from the modern town by worn down ramparts. But they were great for morning walkers and joggers as they skirted the ocean and allowed a view of the old town in the fort and the new town outside as well. Many buildings in the fort have been restored and renovated as hotels, restaurants and boutiques. Indeed, it has become a town for tourists although local life is still visible at school times and around the courthouse.

Most of restored historic buildings are a legacy of the Dutch—a hospital, now shops and restaurants; a Reform church, still a church, but did not seem to be used for worship; a mansion, now a National Museum, which was closed; and the governor’s house, now a luxury hotel. Still, despite the tourist kitsch, it was enjoyable to walk the narrow streets, pass the shops and cafes with tables on the street, while dodging cars and three wheelers driven carefully to avoid distracted pedestrians. The new town was a less interesting South Asian mess, but had an active fish market and a beach that did not look inviting.

Unawatuna, the best-known beach town in the vicinity, a few miles from Galle, has completely gone over to tourism. The narrow winding street off the main road to the beach was chock full of shops, restaurants, lodgings and other services for tourists and the long, deep sandy beach was lined by hotels. Europeans seeking the sun were lying on recliners, moving them around to follow its rays. I spent a couple of hours in their company, taking walks along the ocean to cool off, but the water was choppy and uninviting, especially with a frozen shoulder.

Church, Negombo

Negombo

I chose Negombo, North of Colombo, as my last stop because it is near the airport, to make it easier to catch my very early morning flight on the next day. En route, I had lunch in Colombo with a former colleague that I had worked with on India, who happened to be visiting. Conversation was lively as decades had passed since our last meeting, and much more satisfying than the brief email exchanges in between.

Negombo turned out to be larger and more interesting than I had anticipated. It has about 150,000 people of diverse origins and religions, although mainly Sinhalese. As in other coastal towns of Sri Lanka, the ancestors of Sri Lankan Moors arrived in the 7th & 8th Centuries attracted by the trade in cinnamon, and also brought Islam. The Portuguese followed in the 16th Century and left Catholicism as their legacy. Indeed, a whole clan adopted that religion and Negombo remains about 50 percent Catholic. It has more than 20 churches, several of them cathedral sized. But the lines between religions are blurred as I noticed Hindu shrines in church compounds.

Fish Stall, Negombo

The Dutch supplanted the Portuguese and left buildings and canals. By the time the British took over in the 19th Century, the importance of the cinnamon trade had declined and they preferred Colombo, diminishing Negambo’s prominence. Nevertheless, it continues to be an important hub for seafood, evidenced by the densely tethered boats along the canal and the busy fish market.

My hotel was on the edge of a lagoon and only a hundred yards from the ocean, but neither of those bodies of water were attractive for walking or swimming. A sister hotel on the hotel strip in town had an inviting broad beach, quiet at the tourist end and busy and noisy at the public end with locals enjoying a holiday to celebrate Mahashivratri, a Hindu festival.

Lodging

Hotel accommodation and service were of a high standard, much better than for my visit in 2004. Cinnamon Lake in Colombo was comfortable and within walking distance from the Gangaramaya Temple and Dutch Hospital, two important tourist attractions. The Hill Club in Nuwara Eliya, built by the British in 1930, had updated, comfortable rooms, and shoes, ties and jacket loaners for guests to enable them to use its bar and dining room. The Amaya Hills Hotel in Kandy had colorfully costumed staff and fabulous views, but my room was small, had dated furnishings and several devices such as the air conditioning did not work effectively. The Aliya Hotel in Habarana was my favorite. My “room” was a tent with modern conveniences on a wood platform placed in a forest in a way that the next tent was not visible. Waking up to the sound of birdsong was delightful. The Jetwing in Jaffna was relatively new, well appointed and comfortable. The Tissawewa in Anuradhapura was my only disappointment. The colonial building and grounds were impressive, but my room was tiny and pretty much nothing worked effectively. The Printers Hotel in Galle, a press converted into a boutique hotel, had fine service and eventually I also got a comfortable modern room. On my first night, I was given a huge suit in the main building that had antique furniture and a bathroom bigger than my room at Tissawewa, but it also had a series of dangerously slippery wooden steps. Moreover, a muezzin’s call at 5 am woke me and also the birds, whose complaining chatter would not allow me to go back to sleep. I figured out why I was “upgraded” so I settled for a “downgrade” to a modern, quiet room in their building across the road. Finally, the Jetwing Lagoon in Negambo had a great, big comfortable, modern room, but its location was remote. I would have been better off at either of the Jetwing hotels along the strip.

Sigiriya Rock

Food

My visit was bookended by two good meals, both had crab in a coconut curry sauce, but prepared differently. On my first evening in Colombo, I dined at Semondu, a fusion restaurant in the former Dutch Hospital, which is now a space for upscale restaurants and shops. It was a coconut curry with drumstick leaves and sea crab in the shell served with rice. The curry was smooth and complex and the meal was enhanced by the primitive struggle to crack open the shell and dig out the flesh. It was messy, but satisfying. My last dinner at Lord’s in Negambo, where I had shelled crab pieces in a thick coconut sambal with red rice sprinkled with fried onions and curry leaves and eggplant, was a feast. I used several Lonely Planet recommendations, but Lord’s was the only one that worked–the others were mediocre at best.

Lunches were almost entirely curry-rice buffets at tourist stops mainly because the restaurants feed drivers in the price of the tourist meal. (By the way, in most cases drivers also get accommodation at the hotel where their passenger is booked.) The array of 5 or 6 lightly spiced curries and rice looked impressive, but the temperature of the food was cool, eroding the little taste the dishes had. The buffets at Dambulla and Habarana were a mite better than the rest, but still not memorable.

I was not unhappy with the light spicing, just the cool temperature. When I tried a full-on spicy Sri Lankan curry-rice meal, I got sick even after I toned down the heat with several small containers of yogurt. I tried other Sri Lankan dishes such as Kotthu (stir-fried shreaded roti and vegetables or meat) and a Hopper (crepe made from rice flour in the shape of a bowl with an egg or vegetables or meat), but I found them to be bland because I was too risk-averse to add hot chutney, as Sri Lankans do. I enjoyed the Alfonso mangoes we bought at a roadside stall and let ripen for a few days. They were bigger than the same species in India and succulent, juicy and sweet. The few times I tried western food, it was tasteless, even omelets, and that takes talent.

Ashoka Tree, Kandy

I enjoyed my visit to Sri Lanka and will return for a longer stay. One of my objectives was to visit the sites commemorating the arrival and work of Emperor Ashoka’s progeny for my own research. I am exploring the spread of Ashoka’s governance together with Buddhism as the ideal way to rule (non-violence, tolerance of all religions, and effective concern for citizens’ welfare). Another objective was to find a congenial refuge from Trump’s inane tweets and the media’s endless discussion of them. More concerning is the recent racial violence in the US against Indians. I don’t want to hear “Get out of my country” and be shot, as one Indian was. Yes, within South Asia, Sri Lanka offers the best refuge and Buddhist environment for writing up my research.