India-West Bengal 2017

Palashi (Plassey) is a township on the banks of River Bhagirathi, about 90 miles north of Kolkata (Calcutta), the current capital of W. Bengal, and 30 miles south of Murshidabad, the capital of Bengal in 1757. In those days, Siraj-ud-Daulah was the Nawab (ruler). He had attacked Calcutta to stop the expansion of the British East India Company. As a reprisal, Colonel Robert Clive arrived with reinforcements to expel the Nawab.

Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi

The pivotal battle took place in Palashi. The Nawab had 50,000 troops and the support of the French East India Company, which had a trading post and fort in nearby Chandernagore, and was contending for supremacy with the British in India and Europe. Clive had just 3,000 troops and the guile to bribe several of the Nawab’s commanders, who arrived ready to give battle, but never joined in. Clive prevailed after an 11-hour struggle. Thus began the rule of the British East India Company, and later the British government, over India.

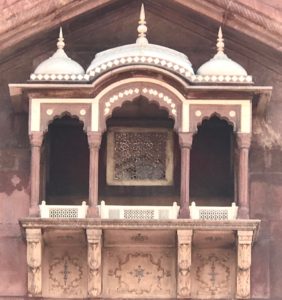

Balcony, Jama Masjid, Delhi

From that time to 1950, Britain’s GDP per person grew fivefold, but India’s stagnated. In 1700, India accounted for about 23 percent of world income, but its share declined to just below 4 percent by 1952. The jewel in Britain’s crown had become among the poorest countries in the world. During British rule, Bengal experienced several devastating famines: in 1770, 10 million people died from starvation; and in 1943, 2 to 3 million people also died. True, the monsoon rains failed, but British policies (East India Company and Government) exacerbated the situation. While all that is in the past, the history of that era should be preserved for future generations in a Museum of Colonial History.

I accompanied a Stanford University Alumni Travel/Study tour as the “academic” to deliver a few lectures on the political economy of India and Bengal. The tour started in Delhi and went on to Varanasi and Kolkata for about two days each, and then we boarded RV Bengal Ganga and plied up and back on the Hoogly and Bhagarathi Rivers through this historic area for 8 days.

Shop around Jama Masjid, Delhi

In Delhi we visited the usual tourist sights such as the architecturally elegant Humayun’s tomb, my favorite monument in Delhi; the towering Qutub Minar; the imposing Jama Masjid, surrounded by a warren of streets clogged with traffic; Gandhi’s memorial; and Rajpath, the majestic, wide avenue from the Presidential Residence down to the National Stadium, lined on both sides by the government’s bureaucratic buildings.

In Varanasi, we visited the wharf where, in the evening, priests perform the Aarti Puja (prayer), now choreographed for tourists watching from boats on the Ganges River. As darkness descended, the cremation ghat nearby was ablaze with bodies on fire, surrounded by mourners. In the evening, we dined inside Rajghat where local Rajas once fed priests. The steps at the entrance steps were lined with rows of small earthen oil lamps, making us feel like dignitaries. The dance performance was graceful and the dinner service attentive, but unfortunately, several of us suffered from delhibelly afterwards.

Aarti Puja audience, Varanasi

The rickshaw ride down to the ghats, through crowded streets milling with every kind of vehicle, person and animal, was harrowing. In contrast, the peaceful park in nearby Sarnath, where Buddha preached his first sermon, was a welcome respite from the noise, and visiting monks from Cambodia engrossed in prayer, added to it.

Cambodian Monks, Sarnath

I had not visited Kolkata for many decades. I lived there during the winter months between 1948-56 when I attended boarding school in Darjeeling in the foothills of the Himalayas. Kolkata was then the leading commercial city of India where many British firms were headquartered. My father worked for one of them, perhaps the biggest.

We did a drive-by of British era buildings, visited a colorful flower market and a street devoted to making clay-molded statues for religious festivals. For me, the highlight was the Indian Museum, the oldest in the country. It had a damaged lion capital for one of the magnificent pillars Emperor Ashoka erected, and remnants of the Bharhut stupa, with its wonderful friezes and carvings, which he may also have constructed.

Flower Market, Kolkata

For me, the visit was also stroll down memory lane capped by an evening with four of my boarding school classmates at the Calcutta Club. Sadly, we were exiled to a far corner of the club because I was wearing jeans, which is forbidden. My appeal that they were made by Armani, fell on deaf ears and a stern look directed us to the hinterland. On our last day, after the river cruise, we visited Mother Teresa’s house and tomb, and the orphanage she served.

Our itinerary on board the Bengal Ganga was designed to show us the remains of several foreign and domestic cultures on the region. In Chandernagore, the former French settlement established in 1688, we wandered along the promenade to the governor’s mansion, now a museum, which showed life in that era with objects and photographs. The French, like the British, recreated their European way of life in India. A short walk past a theater, brought us to Eglise du Sacre Coeur on the edge of a playground where, incongruously, boys in dressed in white were practicing cricket, definitely not a French sport.

Cricketers, Chandernagore

Further along in Bandel we visited a Cathedral built by the Portuguese in 1599, the oldest Christian church in Bengal, and the Hoogly Imambara, a Shia pilgrimage site finished in 1861 in a European style with chandeliers inside, and towers in front with a clock.

In Murshidabad, the Hazarduari Palace, built by a British architect in the Greek Doric style, looked more like a stately home in England than an Indian Nawab’s palace. Now a museum, it housed a collection of antiques. In the outskirts of town was the Kathgola Palace, with an ornamented façade, and an adjoining Jain temple.

Murshidabad, W.Bengal

The virtues of exercise have spread far and wide. At several dock sites, men and women were stretching, walking or jogging in the morning. In Murshidabad, on my walk I noticed a group of men in track-suits, sipping chai after their exertion, with “Hazarduari Morning Walkers Association” in bold on their backs.

In Kalna we walked around Nabakailas temples dedicated to Shiva, 108 small temples actually, arranged in two concentric circles. Across the road, the Pratapeshwar, Lalji and Krishnachandra temples, built between 1750-1850 with some exquisite bas-relief carvings, showed the diversity of Bengal’s temple architecture. Similarly, in Baranagar, the Char Bangla temple complex was constructed in 1714-1793 to resemble traditional village huts.

Kalna, W.Benal

Mayapur, the home of the Hare Krishna movement, has a temple under construction to rival the Vatican in size, partly financed by a scion of the Ford family. When we visited, a huge crowd had gathered to watch a Krishna image being carried to a rath (chariot) and back, accompanied by loud cymbals, drums and chanting by devotees, many non-Indians among them. I was glad to come out of the jostling in one piece and proceed to our ferry through a street lined with kitsch stalls on both sides, an adjunct to many religious places that I don’t appreciate. The next day, the tour group and crew celebrated Holi, a festival of color that welcomes Spring, and allows people to let loose and spray color powder on anyone and everyone, accompanied by music, drinks, and dance.

Mayapur, W. Bengal

Interspersed between visits to historic places, we also stopped at villages. Santipur, where migrants from Bangladesh settled after India was partitioned, and still specialize in their ancestral textile weaving; and Matiari, where craftsmen produce brass and copper handicrafts using age-old techniques. For the visit to the Char Bangla temple complex, we walked through a farming village with adjoining, fertile rice paddies.

Matiari, W. Bengal

I had not been in a village in decades and was shocked to see the level of poverty and lack of progress. Although there were communal water pipes and signs of electricity, people were still living in simple thatched huts. Little seems to have changed in their lives since Independence. Bicycles were prevalent, and an occasional motorbike or scooter, but no piped water or toilets. I did not notice schools in these villages and some young children were running around naked. The main paths were clean, but between every few huts were dumps with mounds of garbage. And these were relatively better-off villages in a fertile area on the tourist route.

Santipur, W.Bengal

Walking through the villages was a visceral reminder that 350 million people still live below the poverty line, as many as the whole population of India in 1947. Although India’s economic growth rate picked up in the 1980s, and especially after economic policy reforms in the 1990s, the large bottom layer of the population has not been lifted out of poverty. The cause is poor governance (ineffective redistribution, inefficiency and corruption)–can’t blame the British any longer.

Lodging and Food

The tour lodged in Taj Hotels in the cities we visited. The accommodations and service were first rate. Years ago when I worked on India and visited frequently, I stayed at Oberoi hotels because of their superior service. In the interim, the Taj Group has upped its game to an international 5 star level. The RV Bengal Ganga had comfortable cabins with modern amenities, and spacious, well-appointed common areas. The crew seemed to be busy cleaning every part of the boat all day.

I stuck with Indian food throughout the trip. Although the spicing was toned down in the hotels and boat, the food was consistently good. At the Taj, the croissants’ crisp and flaky inner layers, my test of quality, pleasantly surprised me.