Bhutan 2014: Buddhist State and Mountains

Walking along the main street of Thimpu, the capital of Bhutan, I really wanted to ask someone if he or she was happy, but I felt shy. Bhutan’s king pioneered the concept of Gross National Happiness in 1972 based on Buddhist ideals that human development has material and spiritual aspects. It provides a more holistic measure of economic and social progress compared to gross national product and rests on four pillars and eight contributors to happiness, reminiscent of Buddha’s four noble truths and eightfold path. After many conferences and comments by international experts, the concept has been bureaucratized with a secretariat supported by an International Expert Working Group and annual “happiness” surveys. In an often-quoted survey done in 2007, Bhutan was the only developing country in the top 20 “happy” countries.

Thimpu has a population of about 120,000 and 30,000 vehicles, but not a single traffic light. Almost all cars stop at crossroads and pedestrian walkways, but there are rogue drivers to watch out for. I heard no road rage or angry exchange during my 9 day visit, even on narrow country roads where a vehicle had to pull over to one side to let the other pass from behind or opposite direction. I saw nothing in the capital or elsewhere in my journey approaching the poverty so evident in India. I can’t say that people looked happy, but they seemed content, superficially at least.

All non-Indian tourists have to go through an approved agent to design their own tour or opt for a standard theme, such as a culture tour, which was my choice. Its emphasis was on Dzongs (fortresses built in the 17 th century to protect against invasion from Tibet), museums housed in their watchtowers, and Buddhist temples dating back to the 7th century when the religion, language and script came to Bhutan from Tibet. The road trip was about 500 miles from Thimpu, to Trongsa, Bumthang, Punakha and Paro. I expected the tour to be interesting of course, but I really wanted to get a glimpse of how Buddhist governance was working.

I arrived in Paro, where the international airport is located, and drove on a highway for 45 minutes to Thimpu. At elevations ranging from 7,300 ft to 8,600 ft, it is situated along the Thimpu Chuu (river) valley and surrounded by higher mountains forested with confirs. In fact, my entire trip remained at about that altitude, although there were higher and lower elevations on the way. Punakha was the exception at 4,000 ft and, for that reason, it is used as the winter residence of the spiritual authority, the Abbot of Bhutan (see below). Although I spent 9 years at school in Darjeeling in India at about the same altitude, I had difficulty adjusting to it in Bhutan. The scenery was familiar, brought back memories from half a century ago, as if I’d never left. The difference, a striking one, was that the mountains surrounding Darjeeling rose higher, to 28,000 ft, with snow-capped Kanchenjunga, the third highest mountain in the world, visible every clear day from the school’s compound, like a center-piece of a jagged, unpolished diamond necklace. I got the chance to photograph it from the plane.

Dzongs dominate the architecture of the five towns I visited, each a district administrative and religious center. They are massive structures with high inward sloping white walls with no windows at lower levels. The upper levels have windows and the walls have a large red ochre stripe below the flared red corrugated iron roof, a modern replacement. They are built on hilltops or spurs for ease of defense, and if built on the side of a valley wall, they have a watchtower uphill. Inside there are complexes of decorated temples, monks’ accommodation and administrative offices separated by courtyards. The larger spaces have timber columns and beams to accommodate huge statues and smaller rooms have carved and painted wood. The entrance is usually a staircase with a narrow defensible entry and huge, heavy wooden gates. Entry to the dzongs is formal as the guides, who have to wear traditional clothes and scarves, sign in their groups.

Among the dzongs, the Trongsa and Punakha locations were striking for their views. The Trongsa structure, in central Bhutan, is built on a spur with a sheer drop on one side. It was covered in fog and mist in the early morning that burned off by the time it opened to visitors. As it is the ancestral home of Bhutan’s royal family, it is huge and richly adorned with colorful paintings depicting Buddhist mythology. The watchtower on a hill above it, quite a climb to reach, has been converted into a museum housing the history of the monarchy and Buddhist art. The view from the uppermost level of the tower is spectacular, bested only by the Tiger’s Nest monastery (see below). Unusually, the Punakha dzong was built on flat land, but at the confluence of two rivers that protect it on three sides. It served as the capital of Bhutan until the 1950s. It looks especially beautiful in the spring when jacaranda trees surrounding it are in bloom. It has a huge assembly hall and mural depicting Buddha’s life. After visiting dzongs in quick succession, they began to look the same inside and I was more than a little dzonged.

Buddhist temples and monasteries are abundant in Bhutan, although none on the same scale as in Myanmar or Thailand. Each dzong has at least one temple, usually more, and there were temples outside the fortresses in each town I visited. Honestly, not being versed in Buddhist religious practice or its mythological arcana, the interiors became indistinguishable after a few temples. Some had bigger or more statues, brighter or larger paintings, thangkas and masks than others. One temple in Bumthang and one in Paro were supposedly built by a Tibetan king in the 7th century; the Kurjey Lhakhang (temple) in Bumthang was a complex of three temples, the oldest built in the 17th Century, dedicated to Guru Rinpoche, the major figure in Bhutanese Buddhism; the Tamshing Goemba (monastery) built in the 16th Century had 100,000 paintings of Sakyamuni; and Chimi Lhakhang, built in the 15th Century, was dedicated to the “divine madman”, a monk renowned for his exploits with women. Because of him, many homes have flying phalluses painted on the outside or wood replicas hanging from rooftops.

The piece-de-resistance among temples was the Tiger’s Nest monastery, just outside Paro. Perched on the side of a cliff about 3,000 ft above the valley floor, it seems an impossible feat of architecture and construction. On the way up to, and from the monastery, the views of the valley and mountains are spectacular. The problem is getting up there. Horses are available for hire, but most visitors walk up, the roundtrip takes about 3 hours. It’s not only the uphill climb, but also the elevation that takes a toll. Deceptively, the path ends higher than the monastery and then a long flight of hundreds of stone steps descend to a lower level and climb up into the monastery. The last flight up seems never ending, but the real catch is on the way back because there are many more steps going up. It’s a relief to reach the path again, although the downhill walk takes a toll on the knees. It’s an effort for sure, but worth it.

House design in Bhutan seems regulated because they look similar, although some are larger or more ornate. Apparently, there is a maximum number of levels to buildings, but that was not evident in Thimpu where construction was active. The distinctive element is the intricate woodwork and painting around windows and roofs. Otherwise, houses and commercial buildings look alike, just higher, wider or smaller.

Thimpu is really the only city in Bhutan to walk around in and get a glimpse of life and commerce. It has a huge week-end market with well-organized sections for products such as vegetable, cheese, grains, etc. and neat stalls. The spice section is aromatic and colorful with vats of red chilies and yellow tumeric. Shops along the main streets were well-stocked and busy, except those selling tourist kitch as the season had not yet begun. I noticed that prices of tourist items such as thangkas and embroidered textiles were much higher than in Nepal. After a search that took me to several art shops, I bought an abstract painting with a Buddhist theme.

Most young people wear modern clothes, mainly jeans, and were plugged in to mobile phones or music, like elsewhere in the world, but traditional dress was in use by the older generation. Men wear a gho, a knee-length robe tied at the waist and women wear a kira, an ankle-length dress with jacket over it. The texture, decoration, colors of these garments apparently indicate social class. Seeing men in ghos shooting arrows at a target in a field near the market is an unusual sight, but archery is Bhutan’s favorite sport.

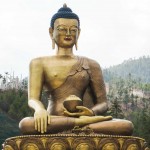

Bhutan’s culture, politics and society are deeply influenced by Buddhism, symbolized by the huge, almost complete 170 ft tall Buddha statue on top of a hill overlooking the Thimpu valley. The country’s constitution emphasizes Buddhism as the spiritual heritage of the country and seeks to promote its principles and values of peace, non-violence, compassion and tolerance. However, all religions are welcome and about a quarter of the population, mostly of Nepali origin, is Hindu and a tiny number practice Islam and Christianity. A major blot in Bhutan’s record of compassion and human rights was the expulsion of citizens of Nepali origin in the 1990s. The UN documented about 107,000 living in camps in Nepal in 2008, about 15 percent of Bhutan’s population.

Although it is a democracy with a constitutional monarchy, the constitution also confirms the traditional Chhoe-sid-nyi system of joint temporal and religious policy formulation. The Buddhist Abbot is the closest and most powerful advisor to the King and the civilian administration. Based on this approach, Bhutan’s governance is the closest I have come across in my travels to Emperor Ashoka’s, spread through Asia as the concept of “dhammaraja” or righteous ruler.

The previous King (fourth), an absolute monarch, devolved power to elected bicameral assemblies governed by a constitution and became a constitutional monarch. Before he abdicated the throne in favor of his son, who is the fifth ruler of the dynasty, he set up independent institutions to guard against abuse of power. Good governance is a priority for the government. It is committed to providing access to quality social services. While poverty still exists in Bhutan, especially in rural areas, it is diminishing rapidly and already the lowest in South Asia. The government provides free education for all through 10th class and further for students that show aptitude. Many go on to college in Bhutan and abroad from public and private schools. Women enjoy rights not available to them in neighboring countries such as a presumptive inheritance right of land ownership. Many marriages occur from choice rather than arrangement and divorce is not uncommon. Men and women share work in the fields and at home, but the proportion of women in senior government jobs is still small. Unusually, killing of animals is against the law, a very Ashokan piece of legislation, but meat imported from India is consumed. Bhutan is easily the least corrupt country in South Asia, indeed all of Asia, except Singapore and Hong Kong, both much richer countries.

Bhutan is as large as Switzerland, but sparsely populated by around 750,000 people partly because it has high and steep mountains crisscrossed by many snowmelt rivers. About 70 percent of its area is covered by forest and only 2 percent is suitable for agriculture, along the river valleys at lower elevations. But, together with animal husbandry, agriculture employs more than half the workforce. Parts of the country have been identified as outstanding eco-regions of the world. The government is committed to maintaining the country’s biodiversity by limiting deforestation and designating 40 percent of the country as national parks. Its biodiversity provides a home for many animals, 770 species of birds and more than 5,000 species of plants.

Despite its small population and difficult terrain, its income per capita is about $6,200, higher than any South Asian country, although donor funds and the Indian government subsidize its budget. Its exports of hydroelectric power to India have helped the economy grow rapidly in recent years. That resource is expected to boost the economy for a long time as Bhutan currently exploits just 5 percent of its hydropower potential and India needs power. With a young population that speaks English, Bhutan has established a Techpark, hoping to expand employment by joining the hi-tech economy. Wedged between two giant neighbors, China to the north and India elsewhere, for historical and expediency reasons, Bhutan has chosen a close relationship with India.

Driving through the country was not easy. Aside from the two-lane highway from Paro and Thimpu, roads connecting the other towns I visited were single lane. Although that slowed movement when a vehicle approached from the opposite direction, it was not the significant impediment. Between Thimpu and Bumthang, a distance of 170 miles, about half the surface was rubble. My four-wheeler jostled at about 10 mph for hours. It was backbreaking. Also, the Indian tectonic plate rammed hard into the Asian plate eons ago, creating close folds in the earth that rose as mountains. The road winds around these folds constantly, adding to the jostling and unsettling the stomach, although I managed to avoid getting sick. Herds of Yaks wandering the road or monkeys crossing were not helpful, but interesting to see. In that vein, Bhutan has a unique animal, the Taksin, its national animal, which has the body of a cow and the head of a goat.

All non-Indian tourists pay a standard fee $250/day to visit Bhutan; in my case it was $290/day because a single person supplement of $40/day was added. For that price, visitors get a hotel, food, transport and a guide. The “tourist” hotels are pretty basic. In my experience, everything worked in only one of the seven hotels I tried. In the others, either the heating or the shower or the internet or the lights or the TV did not work. I switched hotels twice, once because the heating didn’t work and once because the room was dingy. It is possible to upgrade hotels, but the supplement varies from $300/day to $1500/day, out of my reach. Food was not the highlight of the tour. In the hotels, it was generally a buffet. For a vegetarian, I had the choice of cold fried or scrambled eggs and noodles with slivers of veggies. I tried the signal Bhutanese chilies with cheese, but it was too spicy for my palate. I had one decent local meal in Thimpu with my tour agency owner who ordered fried cheese, mixed vegetables, fern curry, mushrooms with chili, egg curry, double wheat chapatti, red rice and white rice with wheat. Only the egg curry had a distinct taste. With it, I drank Ara, a local rice wine like Sake, which tasted better chilled. I also tasted the local vodka and King V whiskey, which was not bad, and Red Panda beer, a Weiss beer made by a small Swiss brewery built by a Swiss who settled in Bhutan.

7 Responses to Bhutan 2014: Buddhist State and Mountains