US Open Tennis 2016

The “thwack” of Janowicz’s serves at 140 mph had a distinctly deeper and lingering sound than even a 130 mph serve. The crazy thing is that Djokovic was returning them near his opponent’s baseline. It was the opening match of the US Open Tennis Tournament for 2016 in Arthur Ashe Stadium that seats almost 24,000 fans and has a new retractable roof. The match started after the opening ceremony with speeches by Mayor De Blasio and Billy Jean King and songs by Phil Collins and Leslie Odom Jr. that were inaudible at the promenade level, high up near god, where I sat.

Unlike skiing or sailing and many other “natural” sports that served a purpose at some stage of human development, tennis is totally artificial. Grown adults whack a fuzzy little yellow ball with rackets back and forth over a three-foot net to land within a marked rectangle. Many earn huge sums of money for doing that well.

I thought Henry VIII started this madness, but no, it was Louis X of France, about three hundred years before him, in the 12th Century. It was played with hands outdoors, like handball, until Louis decided to build an indoor court. After an exhausting game, he drank a lot of chilled wine to cool off and died soon thereafter. I’m not making that up.

Real Tennis Gear

This game evolved into “real tennis”, played with rackets that look like squash rackets, but with a longer shaft, and a harder ball. It is played indoors, off the floor and walls, also like squash. Charles V had a court in the Louvre Palace and I saw one at Queens Club in London in 1958.

“Tennis” is derived from the French “Tenez”. The game we know is actually “Lawn Tennis” and it evolved in the late 1800s after the lawn mower was invented. The first and oldest lawn tennis tournament was held in 1877 at Wimbledon and the first US National Men’s Singles Championship was at the Newport Casino in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1881.

My father, a keen, but untutored tennis player, got me started in a coaching scheme when I was 8 years old. I’ve been involved with the game as a player and a fan ever since, but on and off, for a sweep of seven decades. Other than my connection to India, on and off as well, it has been my longest enduring attachment, like a familiar old friend that I reconnect with every few years.

Mathew’s coaching scheme at South Club in Calcutta produced several international level players. I don’t think I had the ability to reach that level. In any case, I spent just three months of the year in the city and the rest of the year in Darjeeling, up in the mountains, in a boarding school. We were too busy with team sports such as soccer, field hockey and cricket, which were compulsory, to have time for tennis.

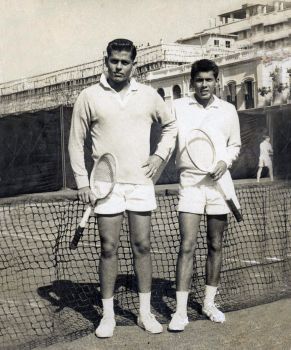

Lall and Mukherjee

When I was about 15 years old, a couple of my peers in the troupe shot past the rest of us. Premjit Lall, a year younger than me, grew over 6 ft tall and developed a quality grass-court game–a high kick-serve that he followed up to the net to volley. In 1958, he lost to Buchholz in the finals of Wimbledon’s Junior Championship. Jaydeep Mukherjee, two years younger than me, lean, and shorter than Lall, had an elegant all-round game. The two of them reached Wimbledon Men’s Doubles Quarterfinals twice.

I went to Wimbledon almost every year from 1958-1966. Premjit gave me passes to the players enclosure for a couple of years, but then I lost touch with him and had to line up with the hoi polloi to get a grounds pass. The most memorable match for me was in 1961 between Ramanathan Krishnan, seeded 5 that year, and Rod Laver, the best player of the era. Krishnan had elegant, smooth, flat and under-spin strokes and great drop-volleys. He was known as a “touch player”, but he was heavy for that level of tennis, waddled around the court, and also had a patsy serve. Despite having beaten many top players, including Laver, he lost the semi-final match.

Laver and Krishnan

At the time, tennis was an amateur sport, not a profession. Players at Wimbledon had their “expenses “covered, but there was no prize money. True, many good players were given sinecure jobs, usually in big companies, which allowed them to concentrate on playing. But these jobs rarely outlasted their playing years and they never earned the big bucks that top players do today. In 2000, I came across Vic Seixas, Wimbledon Champion in 1953, serving drinks behind the bar at my club in California.

Until 1968, the Grand Slam tournaments were restricted to amateurs and professionals had their own circuit of tournaments. Indeed, their level of play was superior to the amateurs. In the late 1950s, I attended a professional tournament at Wembley Arena in London in which Pancho Gonzales and Jack Kramer made quick work of Lew Hoad and Ken Rosewall, leading amateurs who had just turned professional.

When the open era began, and tennis became a truly professional sport, it attracted huge sums of money that drew top athletes who take it as a full-time job and train with the aid of an entourage of coaches, fitness trainers and nutritionists. And they practice and compete virtually year-round. Gone are the days of gifted amateurs winning tournaments.

I attended several US Opens when I lived in New York in 1969-70 and 1977-84, but only one, in 2010, after moving to California. This year, I purchased a ticket plan for the first week of the tournament. In the first few days, fans get to see many new, younger players up close in the outer courts as the stadia are reserved for high-seeded players.

Arthur Ashe Plaza

It was great to see Djokovic’s flexibility and Monfils’ rubbery body and unusual shots from every part of the court and beyond. Wawrinka’s powerful and elegant one-handed backhand, especially down the line, as good as any I’ve ever seen. It helped him win the tournament eventually. Rafa’s whipping forehand that ends with his racket over his head on the other side was as strong as ever, but his game was not as consistent or intimidating as a few years ago. I had hoped to see Raonic go deep in the tournament, but he did not play well and lost in the first round to Harrison. Tomic’s strokes were amazingly smooth, more so than his temperament, which cost him an early loss.

Wawrinka

I expected Nishikori’s all-round game and athletic ability to take him to at least the quarterfinals, but he went a stage further, overcoming Andy Murray in a long drawn-out five setter to reach the semifinals. Hunched Kyrgios looks slightly deranged, but has a good game, although his temperament apparently does not match his ability. That day he was too strong for his opponent. Tsonga, who resembles a young Mohammed Ali, was a pleasure to watch because of his engaging intensity and graceful movement, though not quite Roger Federer’s ballet, who, unfortunately, was not playing. Jack Sock, a new American player, overcame a much higher-ranked, but unusually inconsistent Marin Cilic.

Because of the training regimen, players are lean, noticeably more so than they look on TV. Unexpectedly, although most players are tall, there are several short players competing at a high level. Seeing Del Potro at 6’6” play his countryman Schwartzman at 5’7” seemed an unfair match. I was reminded of Pancho Segura who, at 5’6”, was at the top of world rankings in the early 1950s.

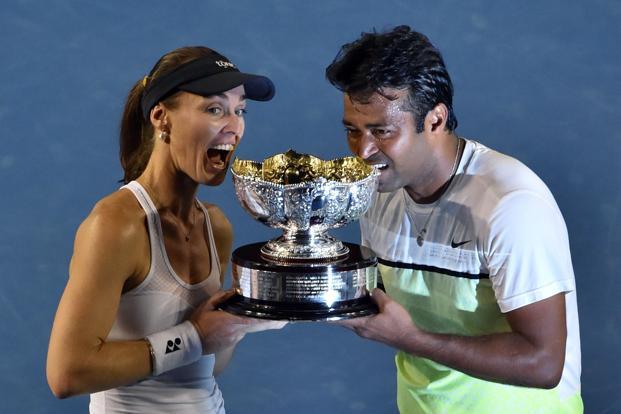

I was surprised to notice the number of seasoned players choking, like my tennis buddies and me. Stosur, a grand-slam winner, blew three match points in the second set of her doubles, lost the set and the match. Leander Paes, with 18 doubles and mixed doubles Grand Slam titles, had a service break to close out his match, but he made four unforced errors, and lost.

Hingis and Paes

Being nervous is understandable for young, new players in a major tournament. Frances Tiafoe from Texas, a rising star, blew a service break at the end of the final set against Isner, who kept his cool and won the match in the tiebreaker. And Naomi Osaka, a formidable player from Japan, could not close her match against Madison Keys despite three service breaks, and eventually lost.

Players can lose concentration and mis-position themselves to make unforced errors on the run, but the number of service double-faults, a stroke that is entirely in their control, was surprising. Because returns of service are so good, perhaps servers feel that have to go for a strong second serve to have any chance of winning the point, and that leads to more errors.

Interestingly, up close, as elegant as the one-handed backhand is when executed well, the two hander has an advantage in returning serves as it has a shorter and more stable back-swing, and the non-dominant hand can direct the ball to acute angles, giving players more alternatives for placing it.

New York’s heat and humidity did not make it easy to watch matches in the outer courts and from un-shaded parts of stadia, except Arthur Ashe stadium in which my seating area was shaded and air-conditioned. I sought refuge there every now and then to recover. On opening night, the escalators were not working so we had to trudge up hundreds of steps to get to our seats. Luckily, no heart attacks were reported. The weather took its toll on players too. Despite their conditioning, many wilted and cramped, and gave up.

The five stadia had another annoying problem. Loud music blared during changeovers, making tennis into a typical American sport. Ear splitting, jingoist chants of “U- S-A” were annoying. I yearned for the pin-drop silence of Wimbledon’s Center Court.

Many spectators were busier looking at their cell-phones than at matches. Worse, the bars on the grounds were packed with people drinking and watching matches on TV. Food and drink stalls and restaurants had us captive, charged outrageous prices for barely edible food.

West Side Tennis Club

One evening, friends invited me to dinner at the West Side Tennis Club, a Tudor mansion, home of the US Open for several decades. It still has 38 tennis courts on four surfaces, besting the Delhi Gymkhana Club where I play on visits to India, which has just 33 courts on three surfaces. The outdoor dining area was beside grass courts with the main stadium, now a performance venue, further back. It is where I saw Guillermo Vilas beat Jimmy Connors in the US Open final in 1977, the last year the championship was held at the club. A spectacular golden-orange sunset and good company made for a perfect evening.

My tennis career was brief. I left India when I was 17 years old and spent 8 months in Nairobi, before joining college in England in the Fall of 1957. With not much else to do, I played tennis almost every day. I wanted to be on the college and university teams and be awarded “colors” for good performance. That happened in my first year, much quicker than I had imagined. The physical arrangements for playing in London were difficult as the college courts were a two-hour train ride away and joining a club in the city was beyond my means. I stopped playing in 1958 when my objective was achieved.

Decades passed while I worked in London, Toronto and New York and played squash, a physically demanding sport, but not of much interest to me. A sporadic, but sustained re-entry to tennis began in 1985 when I moved to Washington DC and had access to public and Georgetown University courts near my home. A colleague at work, Arichandran, a former Davis Cup player for Sri Lanka, spurred me on. I attended a tennis camp to regain my form and, with effort, added modern topspin strokes from both wings. From 2000, when I moved to California, for the first time in my life I played regularly, at least twice a week. I much prefer to play singles, but with advancing age most of my peers gradually dropped out. As a substitute, I joined a doubles team that has been successful in our local league.

What has kept my interest in the game? I am drawn to it because I’m relatively good at it having learned it at a young age as a legacy. Developing the muscle memory for strokes relies on countless boring repetitions, which is much harder to do at an older age. Tennis is a fast-paced, full body and mind sport. Playing well requires good hand-eye and body coordination and an intuitive analytical capability. It is also an elegant sport, especially when played on grass–you have only to watch Roger Federer play at Wimbledon to understand what I mean. The game makes players take full responsibility for their performance, which I prefer to diffusing it among a team.

I’ve returned a tiny bit to the sport that I have enjoyed all my life. In the 1970s and early 1980s, tennis, not a popular sport in the US, was televised by KQED, San Francisco’s public channel. My friend Ken Short was an assistant producer of the program. Knowing my interest in the game, he invited me to join the commentators box for the tournament in Washington DC in 1980. I sat with the great Jack Kramer and Barry McKay and Donald Dell while they talked about the match.

After hanging around for a while, feeling idle, I asked Jack Kramer if there was anything I could do. He said, yeah, why don’t you keep count of aces, winners and unforced errors. A philosophical discussion ensued to define those terms. It’s not as straight-forward as you might think. Barry and Donald chimed in with their opinions while chomping on KFC drumsticks. In the end, we deferred to Jack’s ideas. I then designed a complicated “fence” tracking system for those shots: a row for each with a short vertical line for one occurrence and a line across after four. It was only slightly less complex than the data I was churning through to test an econometric model for my doctoral thesis, which I was working on at the time. Nevertheless, it was fully deserving of the first TV credit as a tennis statistician.

14 Responses to US Open Tennis 2016