London 2017: Hampstead, Theater, Museums

Recently, a friend sent me an email about his lingering attachment to the US where he spent eighteen years, a few as a young boy when his father and I were enrolled in a doctoral program, and many more in early adulthood for higher education and work. He now lives in the country of his birth with his family, but cannot shed his yearning for places where he spent his “formative years”. He asked for my opinion on whether he should pursue a green card application that had been approved.

My advice was to “do it”. Unusually clear coming from a former economist, used to giving two-handed advice—on the one hand, and on the other. Why, because I too have a hankering to live in a place where I spent my formative years, despite seriously mixed feelings about the country and my experience in it. But my longing is more specific—not a country, not a city, but an area within a city—Hampstead, London.

Vale of Health, Hampstead Heath

As a student and then as a trainee-professional, I lived around Hampstead Heath for about six years in several places, and for a year and a half of that on Reddington Road. It was, and still is, a plush street lined with Georgian redbrick mansions, many now divided into flats. The only way to afford living there was to share a three bedroom apartment with two flat-mates and my first serious girlfriend, with whom I was in love, but had no clue what that meant. Perhaps my feeling for her is the reason that I am attached to the street on which we lived.

I had the good fortune to spend a couple of weeks about 200 yards from my former abode. I walked along Reddington Road to Hampstead Heath one morning, startled by the cars and pedestrians clogging the street, people going to work or taking their children to school dressed in neat uniforms, trousers or skirts topped by blazers with a school insignia patch. There weren’t many cars when I lived there, or children for that matter, the street was quiet and traffic flow was smooth. The sound of English English, not just the accent, but also the choice of words, evoked a past familiarity.

Hampstead was known as a residence of the intelligentsia—writers (Tagore, D.H. Lawrence, John Keats), composers, ballerinas, actors (Paul Robeson, Peter O’Toole), artists and architects, and was host to a number of émigrés and exiles from the Russian Revolution and Nazi Europe (Sigmund and Anna Freud). It had a reputation for highly educated liberal humanism or “Hampstead Liberalism”. I have a fantasy to live there as a “lefty intellectual”. Apparently, lefties can’t afford to live there anymore, only people working in finance, and its elected representatives are all Conservatives. In the US, subconsciously, I chose similar places to live: the Village in New York; Georgetown in Washington D.C.; and Marin County in the San Francisco Bay Area. Fortunately, their political complexion remains liberal democratic in the American context.

Vale of Health, Hampstead Heath

I went on daily walks on the heath, discovered new wooded areas, and circumambulated the entire park a couple of times. Weekday mornings were the time for dog-walkers, weekends for joggers, and anytime for amblers and tourists. There is no other place in the world that I know of where, within minutes, you can be walking on country paths and come back to a sophisticated, urbane, urban area easily connected to some of the best cultural assets in the world.

Hampstead Heath Wild Life

Hampstead High and Heath Streets have slick, modern boutique shops, restaurants, antique shops and stalls in narrow alleys, and a community center that hosts a market at weekends. Most pedestrians are youngish and dress the same as everywhere else in the world, ear buds attached to a phone and a messenger bag strapped across the shoulder, but the older generation retains a disheveled absent-minded professor look, men wearing tweed jackets with elbow patches, women wearing coats, and both with hair flying in all directions.

As I grew intellectually at college, I adopted the prevailing form of discourse that ranged over a broad swath of learning and knowledge from many parts of the world. We commonly discussed international political economy, the focus of our education, but also literature, theater, music, art, wine and even a soupcon of sports, and how all these endeavors interrelated to give a fuller, more rounded view of life. It helped that the Royal Shakespeare Company’s theater was across the street and Covent Garden, with multiple auditoria, within 10 minutes walk. You may have noticed that I omitted food as a subject of our conversation. We actually talked a lot about how bad it was, not only English food, but also most other cuisines as well, because they needed to be just a mite better to attract customers.

To be sure, we were far from experts, but the discussions were informed, had enough depth to keep the embers of wide-ranging interests alive for the rest of our lives. When I meet friends from that era, we connect easily, despite our different paths and careers in the ensuing half century. They remain active in politics, business, academia, writing, and acting.

View from Tate Modern

I have seldom found the equivalent companionship in the US, except in New York, which has a deep creative reservoir and a similar European émigré intellectual influence as London. In these two cities, cultural venues are not only abundant and have a high standard, but they are also woven into the fabric of the city. A working person can pop into a world-class gallery or museum during a lunch break. The other places I have lived in the US, Washington DC and the San Francisco Bay Area, do not have anywhere near the same quality or number of cultural resouces. While these places have other attractive attributes, it has been difficult to appreciate the local cultural offerings. It is like having feasted on Michelin three star meals often, and then trying to wax eloquent about a local bistro—it feels false. If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with does not seem to apply.

Besides, Americans seem disinterested in intellectual discussions that are not connected to their field of work. While at graduate school in the mid-1970s, we had a Friday afternoon beer-bash in the courtyard, appropriately called “Liquidity Preference”, where students and faculty would try to shed the week’s tension. I had a standing bet with a few of my classmates: if they engaged a professor for 10 minutes on a subject other than his or her lectures or research, I would buy them dinner. My wallet never suffered the consequences. Probably, the demands of professional competition leave no time to develop other interests.

Man Book Prize reading at Royal Festival Hall

As an aspiring writer, the highlight of my visit was to attend two events related to the Man Booker Prize. Mohsin Hamid’s book “Exit West” was one of six on the short list. I’ve known him for most of his life and am elated by his success. The evening before the winner was announced, all six authors read passages from their books at the Royal Festival Hall. Betraying my bias, I thought Mohsin’s reading was the best because he chose beautifully crafted sentences. During the Q & A after the reading, when someone asked all the authors for advice about writing, Mohsin emphasized reading one’s work repeatedly, to hear how it sounds and affects emotions.

Ladbrokes, the betting service, gave him the second best chance of getting the award. I hoped he would win, especially as it was his second time on the short-list. The next evening we learned that Saunders’ “Lincoln in the Bardo”, the favorite, got the award. Nevertheless, Penguin, Mohsin’s publisher, threw a party for him and another of their authors on the shortlist. It was the first time I mingled with people in the publishing industry. I enjoyed chatting with writers whose work I had read, book agents and editors who gave me leads for my project.

I took advantage of London’s ample cultural offerings by attending five theater performances, three exhibitions and catching a movie at London’s Film Festival. All aspects of the theater performances were excellent, the staging, direction, acting, and in most cases also the story. “Ink” was my favorite. It was about Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of The Sun, a minor newspaper, and the vigorous effort of his editor, Larry Lamb, to turn it into a popular tabloid. The first act of getting the new version of the paper going, upending the prevalent approach to journalism, was full of energy and enthusiasm, including breakouts into Bollywood style song and dance. The second act was slower, ponderous, as difficult issues such as where to draw the line between journalism and pandering nudity to increase sales were confronted. The staging of “Wings” was unusual, an aviatrix who has just suffered a stroke, floating above the stage and also her own consciousness, like a trapeze artist, and emitting garbled sounds. Gradually, she comes down to earth, her speech begins to match what she is trying to say, and her recovery begins. Juliet Stevenson’s performance was extraordinary.

“Beginning” was about the cautious start of a relationship at the end of a party between the hostess, a successful woman in her late thirties wanting a child, and the last guest, a man hurt by a divorce. It was credible, but I found the portrayal of the man less convincing—he seemed too anxious and nervous and not much of an intellectual match for her. In that vein, “Heisenberg”, based on the physicist’s principle of not being able to measure simultaneously the position and momentum of a particle with precision, was the story of a developing romance between a 75 year old butcher and a younger American woman stranded in London, who could have mixed motives, to either ensnare him for money or genuinely care for him. The story didn’t quite come together, but the acting and staging were great.

“Ferryman” was a serious play about a family’s involvement in, and the aftermath of, the Irish troubles, intertwined with a silent, simmering love within the clan. The bloody ending was unexpected, but showed how difficult it is to bury a violent past. The large cast’s acting was superb, but I had difficulty following the Irish accent. “Zama” was a movie made by a renowned Argentine filmmaker. It was based on a novel by Antonio Di Benedetto, which I had read. Set in the 18th Century in a Spanish colony on the Asuncion coast, Zama, a government functionary waits in vain for a transfer out of the unsophisticated, basic outpost, to join his family. The movie took some liberties from the novel, but captured well the languorous life in the colony, but not fully Zama’s sexual hunger or the ill treatment of the natives.

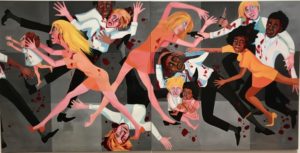

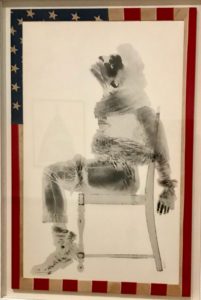

Soul of a Nation

“Soul of a Nation”, an exhibition of African-American art during the Black Power era at the Tate Modern, struck an emotional chord. I moved to the US during the latter part of the movement. Paintings of violence: a lynching next to a Confederate flag; a woman hog-tied to a chair trying to scream in pain; and a riot where bloodied people were running in all directions, were more gripping than portraits of the movement’s leaders. Although much has changed since then, African-Americans are still profiled by the police and treated poorly by the justice system. I timed my visit for the late afternoon so I could have a glass of wine at my favorite bar in London, on the museum’s 6th floor, and get a sunset view of St.Paul’s and the nearby gleaming skyscrapers as backdrops to boats plying the Thames.

St. Paul’s from Tate Modern

In “India Illuminated” at the Science Museum, one section told stories of India’s contributions to mathematics and science, showing the use of the number zero 1800 years ago; a document describing surgical instruments in use in 500 BCE; and bringing them into the modern era with the work of the first Indian to be awarded the Nobel Prize for physics in 1930. The other section had photographs taken by Indians or of India soon after photography became available through the struggle for independence. The faces and attire reminded me of some of my family photographs that date back to about 1920, and the two I have with Nehru and Mountbatten in the viceregal carriage on August 15, 1947 would have fit the theme well.

Soul of a Nation

The British Museum’s exhibition about the Scythians, nomadic tribes that dominated a vast swath of Central Asia and Siberia from 900 to 200 BCE, was surprisingly interesting and informative. The solid gold belt plaques with carved scenes of battles between mythical animals were most impressive, but furniture, clothing and other jewelry were also attractive. As a wandering people, they traded with and borrowed from China, India, Greece and Rome, all settled cultures: silk from China, textiles from India, pottery from Greece and Rome.

Before visiting a friend for dinner, who lives in Hampton, I took the opportunity to get there early to walk through Hampton Court Palace for the first time. The castle is thought of as Henry VIII’s but it was built for Cardinal Wolsey and later seized by the king. Because of Mark Rylance’s brilliant performance in the BBC production of Henry VIII, I imagined him wandering the halls, manipulating people and the polity, rather than the king and his many wives. The grey sky and drizzle dulled the gardens that likely look spectacular on a sunny day.

Having dissed English food of the 1960s, I need to say that it has improved, although I didn’t venture much further than a couple of sumptuous English breakfasts of creamy scrambled eggs with fresh, lightly smoked salmon; and the old faithful pub-grub–fish and chips in florid cuisine language–frontier battered (whatever that is) moist cod, hand-cut browned chips, and battered (smashed) peas. I am partial to pubs, not only for the drink and food, but also because the normally reticent locals converse easily with strangers. One of the assorted jobs I did as a student was to work in a pub behind the bar. The free beer was a good proportion of my earnings. My American girlfriend of the time, dubbed me as her boyfriend, the soda-jerk.

Bar Food Tate Modern

I had a flavorful beet burger that had a novel texture and sweet taste at Bird, a chain restaurant; and another unusual burger, a blend of lobster and crab with herbs, the taste of both meats discernable, at Il Pescatori. My venture into fancy Indian food at Cinnamon Bazaar was a total failure because, in my first course, I bit into a green chili that set my mouth on fire, which I doused with a mango lassi, but I was unable to eat any more.

Having arrived early for dinner at Il Pescatori, instead of waiting there for my companions, I wandered down Charlotte Street into a wine bar that offered about a 100 different wines from moisture-controlled machines. Customers buy a top-up card, say $10 or $20, place the card in the machine slot and press for a sample, a glass, or a bigger glass pour. The concept is interesting, and clearly attractive judging by the jostling clientele. Browsing the selection, I did not notice any American wines on offer. When I asked why, I was told are they expensive for their quality and not food-friendly.

Londoners voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU. Although there is anxiety about the consequences of Brexit, the city remains distinctly international. I heard multiple languages in restaurants, shops and public transport. The weather remains the same as well. I imagine being a forecaster is easy work: it’s sunny, cloudy, and drizzly every day. Only the temperature varies from season to season, and that too not much. London’s transport, especially the Underground and Overground rail system, is convenient and easy to use. The city feels more manageable than New York where pedestrians are dwarfed by a bevy of skyscrapers.

Although the slights I absorbed as a young man still rankle, I recognize that Britain’s decline as a world power, and especially London’s openness to the world, has changed the locals’ outlook. Its tempting to think that my horizons would widen again if I moved back, as they did in my youth, to revive that sense of intellectual adventure. But then again, its always possible that the nativist sentiment that led to Brexit may gather strength to overwhelm London, and I’d have to find a door to escape to Marin, where I now live, as in Mohsin’s novel.