Uzbekistan 2025

Ancient History

Many friends wondered why I wanted to visit Uzbekistan. It has been on my travel list since I researched my book, a biography of Emperor Ashoka, who ruled the Indian subcontinent from about 269 BCE to 232 BCE. During his reign, a thousand monks attended the Third Buddhist Council in 250 BCE. After settling doctrinal issues, the Council sent monks to spread Buddhism. A few centuries later, in 72 CE, the Fourth Buddhist Council was held in Kashmir under the Kushan Empire’s patronage. The empire included modern Uzbekistan and extended over a large swath of Northern India, including modern Delhi. Its greatest ruler, Kanishka, a devout Buddhist, founded Buddhist monasteries and built temples, eventually contributing to the spread of that religion along the Silk Road to China.

Samarkand, Bokhara, and Khiva in Uzbekistan are at the heart of the Silk Road. It connected China with Europe, and trade brought wealth. Consequently, this geographic area was in flux, conquered and influenced by Persia, Alexander, and the Arabs in the seventh century. Samarkand’s fabled riches likely attracted Genghis Khan to conquer it in 1220 and expand his empire westward to the shores of the Danube River.

Amir Timur (Tamerlane), the revered ancient ruler of Samarkand, conquered Delhi in 1398 by defeating its Sultan. Timur spread bushels of fire among the Sultan’s war elephants, who panicked and destroyed their own army. He then sacked the city for three days, killing many inhabitants, and left, taking craftsmen with him. Years later, in 1526, Babur, Timur’s great-great-great-grandson and a descendant of Genghis Khan on his mother’s side, also conquered Delhi but stayed to establish the Mughal Empire, which lasted until 1857, when the British replaced it. Because of this connection, the spoken language of modern Pakistan and North-West India, which I learned as a young person, shares words with Uzbek. I could understand many food names, shop signs, and building names when written in the Latin script, although many are in Cyrillic.

The connection to the Indian subcontinent continued when, in 1966, Soviet Premier Kosygin invited Mr. Shastri, the Prime Minister of India, to Tashkent to meet with his Pakistani counterparts and negotiate an end to the India-Pakistan war of 1965. While there, Mr. Shastri suffered a fatal heart attack and died. The USSR built a monument in Tashkent in his honor.

Recent History

More recently, in the nineteenth century, the Uzbekistan area was a part of the “Great Game”, in contention between the British and Russian Empires. The latter eventually prevailed and dominated Central Asia since the mid-1800s. Later, it became a part of the Soviet Union as the Uzbekistan Soviet Socialist Republic. According to our guide, people here remember the Bolshevik period as hopeful, Stalinist as nasty, and post-WWII Soviet (especially Brezhnev’s rule) as secure.

Uzbekistan became an independent country in 1991 when the USSR dissolved. Like all former Soviet Union countries, it experienced a difficult political and economic adjustment. Many men and women went to prosperous countries to work in the transition. As its economy stabilized and the polity liberalized, some returned.

It is a secular state with a constitutional government. Islam Karimov, the first president, was authoritarian, but his successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, has implemented reforms to liberalize governance and the economy, which is transitioning from a government-controlled to a market economy with a convertible currency and a stock market. Uzbekistan has gold, copper, uranium, oil, and gas deposits, and also exports cotton. Its per capita income is about $3,000, but the country feels considerably more prosperous than that number suggests. It has followed a state-directed import substitution development strategy but is gradually opening up to private domestic and foreign investment.

Most Uzbeks follow Islam, but some follow Russian Orthodox Christianity, Judaism, and Buddhism. People learn Uzbek, Russian, and Tajik, but most of the conversation I heard was in Russian. Many have East Asian features, including a few hundred thousand Koreans resettled in Uzbekistan by Stalin. Food is similar to Turkish, with various Kebabs and salads including fresh, tasty vegetables, especially eggplant and beetroot.

Tashkent

I landed in Tashkent about half past midnight after two long flights, ten hours from Washington, DC, to Istanbul, a three-hour layover, and then a five-hour flight to Tashkent to join an Overseas Adventure Travel tour group of nine travelers. As I alighted from a bus and entered the terminal, I noticed long lines at all ten immigration booths. I was tired and felt disheartened, but the process was quick. As I had no checked luggage, I exited the terminal quickly and searched for a taxi. It was crowded outside with people who looked like Islamic pilgrims searching for transport–a third-world melee. Luckily, a taxi driver found me, showed me his credentials, and quoted a fare below what I had been told to expect. He weaved his Chinese-made BYD electric car carefully through the crowd and onto wide, well-lit boulevards to the Lotte Hotel. I asked him about his car, which had a luxurious, modern interior, a sizeable monitor, and a quick-charging battery. He had paid $21,000 for it.

Built in 1958 in the Soviet era to accommodate writers from Asia and Africa, the Lotte Hotel had classical architecture reminiscent of country estates. Jetlag jarred me awake early the next day. I walked in the crisp sunny morning near the hotel, noticed the majestic Navoi State Opera and Ballet Theater opposite, with a fountain in front, built by Japanese prisoners of war, as I learned later. I walked along Islam Karimov Boulevard with three lanes each way, filling up with traffic, its sidewalks being cleaned by a bevy of middle-aged women in traditional dress using wide natural brooms, past ministry buildings and the central bank. There was a lush green park with a café every few blocks. I noticed many Chevrolet cars on the move or parked, more than anywhere in the US. I later learned that they were assembled in Uzbekistan and had a virtual monopoly until recently, when Daewoo, BYD, and others were allowed to do the same. That first walk certainly disabused me of the notion that Uzbekistan was a third-world country.

Tashkent was devastated by an earthquake in 1966, with its epicenter in the middle of the city. Most structures, including old archeological sites, were destroyed, except for the stolid Soviet-style buildings. Soviet Chairman Brezhnev visited, and rebuilding started with the help of workers from other Soviet Republics. Like other Soviet cities, Tashkent has wide boulevards lined with sturdy buildings, and modern steel and glass structures added since independence. Many of the workers remained in Tashkent afterwards, changing the ethnic composition of the city.

The tour company had not arranged much of a program for the first day, just an orientation walk around the neighborhood, which I had already covered in the morning. I met my fellow tour members and three of us had a light dinner in a café nearby, and then went to the Uzbekistan Conservatory of Music to hear a visiting Frenchman perform a medley of French composers—Chopin, Ravel, etc., for about an hour in a sizable auditorium at the back of the building. The audience appreciated his performance and asked him to play several encores. As we walked to the front of the impressive building, we noticed that many new high-rises nearby were lit in changing multicolored light patterns, like a light show.

Tourism started on the next day. This included the Hero Monument, a massive statue of a man guarding a woman against the shifting ground, commemorating the earthquake of 1966; Independence Square, celebrating the break from the Soviet Empire in 1991; and another park, in remembrance of the men that died (538,000) in, and were missing (128,000), after World War II. After that, we strolled to the Parliament building, a newish Soviet-style structure, and then walked around a Romanoff villa, now a museum closed for renovation. Finally, we went up to an observation deck at the Uzbekistan Hotel to view the Timur monument set in a lush park, and the city. It is well-covered with parks and greenery along the wide boulevards.

The next morning, we drove through morning traffic to walk around the Barak Khan Madrassa, which was under construction and had one of the oldest Korans on display nearby. We walked through Chorsu (crossroads) Bazar in what remains of the old part of the city. The huge establishment is divided by product type, such as bread and confectionery, meat, eggs, dried fruit, and cheese. The aroma of fresh bread baked in Tandoor ovens was appetizing. After walking through the extensive bazaar, we took a subway ride to the Astronaut stop near our hotel, where our guide gave a lecture on the Soviet Space Project and Uzbekistan’s participation in it. After another lengthy ride through traffic, we reached the Central Asian Pilaf Center, a prominent place preparing vast amounts of Plov, the local version of pilaf. We were lucky to find a table for eight people in a vast hall. The plov was decent: rice with beans and raisins fried in oil with meat flakes sprinkled on top. It was heavy but helped down with thick and creamy yogurt.

There was no need for dinner in the evening. Instead, I walked the length of Broadway Alley, an active street with food stalls, street artists, playgrounds, etc. near our hotel and stopped at “Just Wine”. There, I enjoyed two excellent wines from the MSA Family Winery—a full-bodied dry Riesling and a Bayan Shirey, a local grape, that was a lighter dry white wine. I was particularly impressed by the quality, as I hadn’t expected to find wine in Uzbekistan.

We ended our 14-day tour back in Tashkent for part of a day, with enough time to visit the Museum of Applied Arts, housed in a mansion formerly owned by a Russian diplomat. The museum had displays of traditional art—-woodwork, metalwork, jewelry, ceramics, rugs, wall-sized paintings in the miniature style, and traditional embroidered clothes. It was an impressive and representative collection of Uzbek crafts. I also had time to enjoy a last glass of Bayan Shirey wine at Just Wine, before our sumptuous farewell dinner at a swish restaurant near our hotel, ending with farewell speeches.

Samarkand

We traveled southwest from Tashkent to Samarkand by coach, covering the 200 miles in about five and a half hours on a two-lane intercity road that was not well maintained, and the rest stops had not been modernized to accommodate tourists from affluent countries. The landscape between the cities was flat and green, planted with grain and vegetables. We passed villages with simple dwellings made of concrete bricks and covered by a corrugated tin roof. I noticed that the doors to homes in villages, towns, and cities were ornately decorated.

Like Tashkent, Samarkand has wide boulevards, although the buildings were not as new or high and in the Soviet Modernism style. The city felt more comfortable and manageable. Samarkand is one of the oldest cities in the world, established in the eighth or seventh century BCE. Being one of the prominent cities along the Silk Road, it too has been captured by prominent invaders through history. But now, it feels dedicated to Amir Timur. Our hotel was between an imposing statue of him in a traffic circle on the left and his mausoleum on the right.

Timur Mausoleum Entrance

Our first visit was to his grandson’s observatory. Ulugh Beg was an intellectual rather than a warrior. He spoke several languages and excelled in mathematics and astronomy. His observatory, found by Vasily Vyatkin in 1908, was the finest of his era. Ulugh Beg was considered an accomplished observational astronomer. He built madrassas to pass on a legacy of learning, and the Timurid dynasty reached its cultural peak during his brief rule.

Ulugh Beg completed Timur’s mausoleum. It was designed mainly by an architect from Isfahan, utilizing the decorative style of that city with carved bricks and mosaics. The main section is a highly decorated octagon that houses the crypts of several Timurids. The dome, azure on the outside, is said to be the prototype of Humayun’s tomb in Delhi and later the Taj Mahal in Agra. As it began to drizzle, I returned the next morning to appreciate its beauty in sunlight.

Timur Mausoleum Crypt

Later that morning, we visited the magnificent Registan Square with three madrassas composing a vast public square buzzing with tourists on a sunny morning. They were built between 1420 and 1636 and survived several earthquakes. The Soviets restored these masterpieces, and later, UNESCO did as well. The highlight is the mosque in the central madrassa. It is on the left-hand side of the courtyard and is intricately decorated with blue and gold to symbolize Samarkand’s wealth. The delicate ceiling, with abundant gold leaf, is flat, but its tapered design makes it look domed.

Registan Square

We left the square to walk along a broad boulevard closed to traffic, with upscale shops and restaurants on both sides, to visit the imposing Bibi Khanum Mosque, which, in legend, was a gift to Timur by one of his wives. Its complex construction has three domes, four minarets, an intricate, colorful ceiling and mihrab, and a vast courtyard containing a huge Quran stand made of marble. The Soviets restored it as it had fallen into disrepair. In the afternoon, we visited Shah-i-Zinda, the mausoleum of a cousin of the Prophet Mohammad who is thought to have brought Islam to the area. In reality, there was a series of mausoleums along a narrow alley, some elaborately decorated and others not.

Golden Mosque Ceiling

The next morning, we drove to a village on the outskirts of Samarkand. The city ended abruptly, and we traveled on a potholed road through lush green fields planted with various vegetables and some vines. We stopped at a family home, with a section for parents and one for communal dining. We hiked up a hill and enjoyed a view of the village and the stream flowing through it, sheltered under a mountain.

Golden Mosque Mihrab

I skipped a discussion of arranged marriage in the afternoon as I was familiar with the subject from my youth in India. Instead, I returned to Registan Square, wandered through the square with fewer tourists, and walked down to the Bibi mosque. On the way, I ducked into a building that housed artists and craftsmen, hoping to find an abstract painting to commemorate my visit, but the only atelier with that type of work was closed. Back at the hotel, I enjoyed a view of the sunset from the hotel’s roof deck while eating a shrimp salad from a local restaurant, accompanied by a glass of Bagizagan dry white wine from Samarkand, which was potable, but not as good as the MSA Family wines. As Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked country, meaning all its surrounding countries are also landlocked, seafood is scarce. That was my only taste of seafood in Uzbekistan, and I had to shift my pescatarian diet to vegetarian.

Bukhara

We left Samarkand for Bokhara on a fast train. The train station was modern, and the trip, which took less than two hours, was comfortable, as good as the Shinkansen trains in Japan and just as punctual. The landscape was flat, with some areas planted and green, while the unirrigated regions appeared arid with shrubs. We passed through some small, impoverished villages, but the towns looked newly built and modern. Our bus picked us up, and we drove through a semi-urban area along a poor road to Bokhara. Our hotel was close to the Old City, the main tourist attraction.

Bukhara Dancers in the Park

Our trip leader escorted us to the main square, which is bordered by two caravanserais with a park in the middle and a mosque and shops on the sides. He told some of Bukhara’s history during the Silk Road era. We visited a nearby synagogue and were informed of the sizable Jewish settlement for centuries and their recent migration to Israel. We then walked a little way through the market, stopping at the gallery of a master miniature artist. His paintings were good, but not to my taste. On the way back to the hotel, I bought a cold bottle of Uzumfermer Chardonnay, a Tashkent winery, and had a glass before dinner. It was full-bodied and fragrant.

Bukhara Musicians in the Park

At about 7:30, we walked to a restaurant in an old house near our hotel. With dinner, we got a brief dance and music show–a small guitar-like instrument and a simple tabla-like accompaniment to a dancer whose movements were similar to Indian classical dance.

We visited the Ismoil Sominy memorial in the morning, a Zoroastrian building. He founded Tajikistan, and the region’s currency is named after him. We continued to the Chashma Ayub mausoleum and the legendary spring, ending the morning at the Ark Citadel, the city’s fortress and the site of the beheading of two British soldiers during the Great Game. We had lunch at a restaurant near the hotel, where the salads were good, and I saved some for dinner. We walked through the extensive bazaar with a few commercial stops in the afternoon and ended at the Kalyan minaret and mosque. I visited a fancy carpet store and browsed in a shop that used an Ikat weave, but both were pricey.

Before it became hot in the morning, I walked around the labyrinth of lanes with shops in the old city. Bukhara is a vast bazaar that sells various things to tourists nestled among the monuments, just as it did during the Silk Road era. We spent the rest of the day with a family in a village, preparing and sharing lunch with them, which I will write about below. We returned to town at about 3 pm. Our trip leader took me to a gallery where I liked two abstract paintings by the same artist. After staring at both for a while, I made my choice. Packing it as check-in luggage was challenging, but it was accomplished eventually. Here is a brief edited comment about the artist: “Since 1978, Abdullaev has actively participated in national and international exhibitions; in 1988, he joined the Artists Union of Uzbekistan, and was awarded the Gold Medal of the Academy of Arts (2007). The art of Muzaffar Abdullaev’s temperament is raging in his canvases; paints seem to be flowing from his fingers, creating a turbulent action on the canvas…Depicting his vision of the world with the language of colors, he invites the viewer to reflect on life and its joys, past and present, while maintaining the national style of his visual language – a peculiar one, akin to music.”

Abdullaev Painting

Khiva

The drive to Khiva took almost 8 hours after several short stops and a longer one for lunch. The first half of the drive was smooth on a concrete road, but after we crossed the Amu Darya River, the road became bad, The landscape for the first half was arid steppes with small bushes protruding from caked earth, and then it became a desert, soft granular sand with an occasional hard-scrabble plant rising out of it. The landscape turned green with irrigated farms planted with various vegetables just before reaching the river and afterward. Incidentally, the Amu Darya no longer reaches the Aral Sea, which has been drained for irrigation. The inland lake is considered a salient ecological disaster.

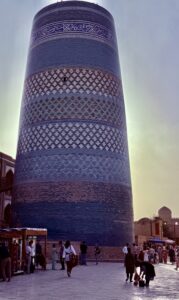

Khiva Blue Minaret

Legend has it that the oasis of Khiva is where Shem, son of Noah, discovered water in the desert and joyfully shouted, “Hey va.” It is now a spruced-up living museum known for its many minarets. Our modern yet simple hotel was across the street from one of the entrances to the old city. Our guide walked us to the fort, which serves as a vast marketplace for tourist trinkets, featuring small shops and stalls throughout, especially near the four minarets for which Khiva is famous. People also reside in the expansive fort area, which includes several restaurants. After the tour, I explored the town independently and returned at 7, just in time for dinner.

Khiva Big Minaret

We walked around the old city all morning, visiting the Tash Hauli Palace, which included the inner courtyard and throne room, the rebuilt Dzhuma Mosque, and Kunya Ark, the original residence of the Khans, featuring a mosque, a reception hall, and a harem. It was a fantastic stroll through Khiva’s past, reconstructed with UNESCO’s help. The temperature reached 100°F, which didn’t help. After the long walk, we had lunch at a restaurant in the old city. Following lunch, I tried to get cash from an ATM, but it swallowed my card, which took me about 1.5 hours to retrieve. Later, I joined the group for dinner on the rooftop of a restaurant in the old city. The night lights and the ensuing fireworks show were terrific, making the dinner magical.

Khiva Musicians

Nukus

After a leisurely morning, we set off for Nukus, our last city. The road was not good for the most part, so the going was bumpy and slow. The landscape was not interesting either—green and planted to crops with irrigation, and hardscrabble soil where it was not. We went through several villages and small towns and arrived at Nukus around 5 pm. We were close to the dry Aral Sea in an autonomous area called Karakalpakstan. This area was “closed” under the Soviet regime because the army used it for research into chemical weapons. I walked a few blocks to the local market and stopped at a beer shop to exchange words with a few locals. We didn’t get far because I don’t speak Uzbek or Russian and they didn’t speak English.

Alexander Volkov

The main site for us here was to visit the Nukus Museum. Its avant-garde art collection is one of the finest in the world, second in size only to that of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. It was established in 1966 by Savitsky because he collected most of the exhibits, and became the museum’s first curator. Savitsky wanted to inspire the next generation of Karakalpak artists and began collecting works by modern Central Asian artists. He also purchased artworks by Russian artists who had painted in, or were influenced by, Central Asia. The vast majority of artworks he collected were not put on show in the museum until 1985, a year after his death, and it was after the Independence of Uzbekistan in 1991 that the full extent of the collection, and its importance, was realized. We were given a two-hour tour guided by one of the curators. I especially liked Alexander Volkov and Vassily Lysenko’s paintings.

Vassily Lysenko

After the long visit to the museum, we had a delicious and filling meal at a nearby Turkish restaurant. Then, I wandered around the town looking for packing materials for the painting I purchased. I did not succeed, but the hotel came up with a used cardboard box that fit the painting well. The next day, we took a flight to Tashkent, which was late of course, but we got there with enough time to do our last bit of tourism and enjoy a farewell dinner.

Locals

The tour company makes appointments with locals to give travelers a flavor of life in the country. In Tashkent, a gentleman gave us his thoughts on Soviet rule and the difficult transition period when it was hard to find work and also to pay for services that had been free. I was familiar with this plight, having worked in Azerbaijan in the mid-1990s and Tajikistan in 2009.

In Samarkand, the daughter of a family accompanied us to her home in the suburbs. We entered through a large, high gate into a rectangular compound with open space in between. It housed elderly parents and their son’s family with two daughters. We were directed to a kitchen and dining area, which was especially for guests. We chatted with the daughter and her cousin, who spoke English, about their daily lives. The husband, an English teacher, arrived later and told us his story of working for years in Brighton, England, and San Francisco, US, in basic jobs like dishwashing to support his family in Tashkent. The good outcome of the difficult period was learning English and now earning a living teaching it.

Rooftop Dinner Khiva

On another day in Samarkand, the group met two ladies, one whose marriage was arranged and the other who had chosen her own husband. About 60 percent of marriages in Uzbekistan are still arranged. Coming from India, I was familiar with this dilemma, as about 90 percent of marriages are still arranged. On one side, making one’s own choice for such an important aspect of life is crucial. But this choice is often made at an immature age when decisions may not be appropriate and, in any case, a couple can grow apart. Conversely, an arranged marriage is a contract with another person and family of equivalent social standing. This contract is bolstered by the families and affection between the couple can grow over time and also can be enduring.

Khiva Old City Wall

From Bukhara, we drove to Nayman, a village with about 3000 residents. We talked to the mayor, a former policeman, about the village and his job of providing needed services when many young people leave the village in search of better, modern opportunities. As we walked to a family compound, boys and girls from nearby school came to talk to us about their ambitions. English was among the languages they were learning. We entered the compound through a similar high gate. Like the other family visit, it was rectangular, housing a joint family, but the open middle section was planted with vegetables and fruit. We helped them plant tomatoes and also make a traditional lunch of plov, somsas, fritters, and salad, which we later enjoyed in the guest dining room. The host had been a medic in the army and later worked in a hospital until he retired. I believe his son worked in town in the tourism business.

Ashok as Emir of Bukhara

These arranged meetings feel somewhat staged but are worth the effort as they convey a little of life in the country. In contrast, on the two Stanford Alumni trips I accompanied as a professor, the travelers did not meet a single local person.

Hotels and Food

Our guide mentioned that the tour company chose the hotels because of their location, which was accurate for all of them. Beyond that, only the Lotte Hotel in Tashkent, a member of a Korean chain, was comfortable. In contrast, Sultan Boutique in Samarkand, Amelia Boutique in Bukhara, Asia Khiva in Khiva, and Jipek Joli in Nukus were adequate two-to-three-star hotels.

As I mentioned earlier, since Uzbekistan is a double landlocked country, the protein in every meal was some kind of meat. I adjusted my pescatarian diet to vegetarian and was quite happy with the variety of soups and salads, in which the vegetables tasted better than those in the US. The accompanying Tandoori bread was also fresh and good for sopping up the dressing.